It is nearly the end of 2013, and everything that we can do

this year can only be done in the next six hours.

But while it is December 31 2013 in the Gregorian calendar, it

is also 28th of Tevet, 5774 in the Hebrew calendar and so from another perspective,

there’s still lots of time to do something meaningful.

Viktor E. Frankl is a man with no time left on this planet

in any calendar. He will never feel the sun on his face again. Or swim in the ocean or learn something new

or listen to music or be with the people he truly loves.

He died 16 years ago, but I'm grateful he lived and worked because he helps me make sense of my world in a profound way. In my favourite passage in his book Man's Search for Meaning, he writes about another ending he witnessed in the Holocaust:

“This young woman knew that she would die in

the next few days. But when I talked to her she was cheerful in spite of this

knowledge.

"I am grateful

that fate has hit me so hard," she told me. "In my former life I was

spoiled and did not take spiritual accomplishments seriously."

Pointing through the

window of the hut, she said, "This tree here is the only friend I have in

my loneliness." Through that window she could see just one branch of a

chestnut tree, and on the branch were two blossoms. "I often talk to this

tree," she said to me.

I was startled and

didn't quite know how to take her words. Was she delirious? Did she have

occasional hallucinations?

Anxiously I asked her

if the tree replied.

"Yes."

What did it say to

her?

She answered, "It

said to me, 'I am here-I am here-I am life, eternal life”

She might have died unnoticed

And unknown,

But there was someone was there

Who listened

And wrote about what he heard

And was part of the ripple that began with her experience of life, that reaches me today

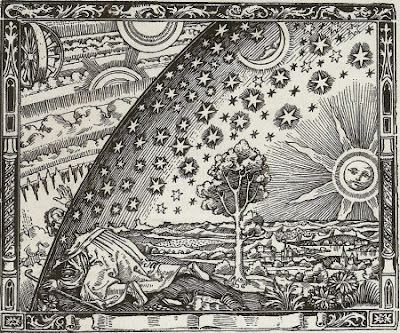

We live in the illusion of limits, but it’s only when we see

the limits

that we can glimpse at the power behind the illusion.

that we can glimpse at the power behind the illusion.